By Sebastian Sheath

Warning: This post contains spoilers for Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014).

Ex Machina is probably my favourite film of all time. Not only is it visually impressive, suspenseful, and well constructed, but it also poses interesting questions for the viewer, potentially causing them to re-evaluate their morals. With an excellent, thought-provoking script from Alex Garland, author of The Beach and screenplay writer for 28 Days Later, the characters are some of the most complex and interesting characters in cinema. This makes the film elaborate enough to be interesting on every rewatch, but not so much that a first viewing is confusing. Why does this film work so well? What questions and concepts it poses and how practical are they?

What IS True AI?

The nature of consciousness is one of the film’s biggest themes. The film itself centers entirely around the Turing Test that Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson) conducts to decide whether Nathan (Oscar Isaac) has truly created a conscious machine and it delves into how to test whether Ava (Alicia Vikander) is truly intelligent or not.

The film discusses simulated AI verses true AI early on. In a real Turing Test, the person/robot that you are communicating with is hidden behind a wall and the tester must decide whether they are talking with a human or a machine. This means that, though the machine is not intelligent, it can simulate a human response (though it does not truly understand the conversation). This is where Ex Machina differs from a normal Turing Test – the tested is shown to be a machine before the test and the challenge, instead of seeming conscious, is to prove that the machine is truly intelligent (and not simply imitating intelligence).

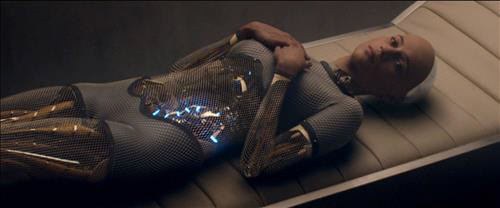

Ava’s self-awareness is displayed early on when she makes a joke and fires one of Caleb’s comments back at him. The repeating of one of Caleb’s comments shows that, not only does she have a true understanding of the conversation on a larger scale, but she’s also aware of herself and is capable of manipulating herself and others. This self-awareness is also shown in Ava’s desire to be human. She puts on clothes to appear human, expresses her urge to go ‘people-watching’, and, at the end, as she takes the skin of the earlier models and becomes seemingly human.

The Grey Box

Consciousness Without Intelligence

Ethical Uses Of AI

Kyoko (below) also brings up the issue of ethical uses of AI. Her inclusion explores the idea of AI enslavement. If you have created a being, do you own them and do they, if they have no emotion, deserve rights? Throughout the film, Nathan sides with the idea that the machines that he has created are his and, as they cannot feel, don’t need to be treated well.

When asked why he created Ava, Nathan replies ‘wouldn’t you if you could?’. Though brief, this interaction explores the ethical issues of the creation of AI and the idea that, if you could create a consciousness, should you, and if they don’t have emotion, should their living conditions factor into your answer?

Not Human, Not Conscious

“So in that scene, what used to happen is you’d see her talking, and you wouldn’t hear, but all of a sudden it would cut to her point of view. And her point of view is completely alien to ours. There’s no actual sound; you’d just see pulses and recognitions, and all sorts of crazy stuff, which conceptually is very interesting. It was that moment where you think, ‘Oh she was lying!’ But maybe not, because even though she still experiences differently, it doesn’t mean that it’s not consciousness. But I think ultimately that maybe it just didn’t work in the cut.”

Honestly, I’m glad that the scene did not make the cut, but it does look at many of the same questions, though in a less subtle fashion.

“Now I Am Become Death, Destroyer Of Worlds” – J. Robert Oppenheimer

It is hinted at, in the scene following the second power cut, that Nathan may have orchestrated the power cuts himself to see how Ava and Caleb would act unobserved and to test if Caleb is trustworthy or not.

Nathan’s struggle with the morals of his own actions is also shown as he quotes Oppenheimer. Both of the Oppenheimer quotes that are brought up are quoted, in turn, from Hindu scripture and explore Nathan’s belief that he may be creating beings only to kill them immediately after, causing him great guilt.

“In battle, in forest, at the precipice in the mountains, On the dark great sea, in the midst of javelins and arrows, in sleep, in confusion, in the depths of shame, the good deeds a man has done before defend him.”

Somewhere In Between

The final two points are less philosophy-based and look more at the technicality of building an AI and the idea of language being learned. First of all, in the below scene, Oscar Isaac’s Nathan shows Caleb that Ava does not use ‘hardware‘ as such, but instead uses a substance that constantly shifts and changes, much like the human brain. This is a really interesting concept as it overcomes the issue of the human brain. This is a really interesting concept as it overcomes the issue of the human-like brain being designed with an exclusively boolean data system (1 or 0, nothing in between).

I hope you liked this post and be sure to let me know what you think in the comments. Also, be sure to check out my sci-fi reviews at The Sci-Fi Critic, my review of Wes Anderson’s Isle Of Dogs, and my article on What Went Wrong With Annihilation.

Sources: Den of Geek

I recently stumbled (again) on this debate. We used to talk about it in SL a lot, a decade ago, and it was part and parcel on the EXTRO usenet group in the 90s, and it remains a compelling concern today, probably more so considering advances in self-learning algorithms. Just the other day it also came up on the reddits, and here was my respons – (slightly edited)

Intelligence is a unpleasantly confusing concept. It’s a clumsy word. It’s so clumsy you’d literally would be unable to define it in a way that’s even remotely unambiguous. Similar words and phrases are “having a soul”, empathic, self-aware, conscious, sapient, sentient, intuitive, creative, “problem solving”, smart, “having cognition”, “having ambitions”, “having desires”, “being able to want” and many more.

There’s the distinctive possibility that we as humans are a lot less sentient we assume we are. It may be that our ability to process meaning is a lot more narrow and less universal than we assume. It may be that we are in essence unable to come to terms with the concept of intelligence (or all of the above), define it, properly parse it and replicate it outside the human mind, and then make predictions about it when it does emerge in the world.

I am concluding that what we make may or may not be labelled as “smart” or “intelligent”, but it sure as hell will be capable of doing things potentially, unimaginable, plausibly more unpredictable and thus frightening, than humans. Intelligence may be a vague conceptual field that overlaps with all the other equally nebulous blotches of concepts above. My point is that once we make what we’d call AI it can be a bunch of different blotches that are quite well capable of functioning meaningfully and independent in the real world. These things would provide services, and make money and solve problems, if they “wanted” (again, a nebulous concept) it.

My take is that human intelligence being so specialized, it has massive emergent prejudices, narrow applications, and thus lots of stuff it can’t do that engineered or algorithmic or cobbled together or synthetically evolved functions or machines would be frighteningly good at.

These things would very well be capable of do things previously regarded as impossible, and we as humans would be confronted painfully with our own striking non-universal intelligence that we’d be completely incapable how these things do what they do, even without these things being super-intelligent. It may turn out even fairly early steps in AI may resolve to produce wondrous machine minds doing positively inexplicably wondrous things, achieving inexplicable wondrous results.

And even though there would be some long-term problems with “utterly unempathic” superhuman intelligences, we’d be a major hurt well before that, as people owning these new devices would then be able to

*circumvent laws

* lobby highly effectively in government

* avoid (paying) taxes

* create technologies and devices unimaginable before

* engage in various forms of violence

* manipulate human minds very effectively, and on a large scale

That sweaty asshole Mark Zuckerberg became a billionaire with a stupid ‘facebook’ that got wind-tunnelled in to the biggest espionage monstrosity humanity has ever seen. In a decade. Facebook is now so important a monstrosity that it has completely escaped the ability of politicians, people, the law, science, democracy, the economy etc. to control it. And that’s just early days. There will be many more so monstrosities and their emergence will be quicker and quicker. Eventually you will have apps (tools, algorithms, machines, whatnot) that emerge in months, sweep the human sphere in days and have unspeakable impact on our world.

It could get ugly, especially when ugly people retain exclusive rights to command these Djinn to unilaterally do their bidding.

LikeLiked by 2 people