It’s a small miracle really: the recent Netflix premiere of Orson Welles’s lost final film, The Other Side of the Wind. It’s something akin to locating the Titanic or perhaps resurrecting a living breathing woolly mammoth. And the achievement isn’t merely about finding the film: this is the real deal, a genuine masterpiece from a genuine master filmmaker believed lost to history forever and suddenly against all odds unearthed. It isn’t merely an oddity: as a film The Other Side of the Wind stands on its own merits, a final bookend to a brilliant, if enigmatic career.

The film’s history goes something like this: in 1970, Welles, at the age of 60 returned to Hollywood from retirement and seclusion in France to begin work on a new film, what promised to be a groundbreaking picture from a man whose entire career had been about breaking new ground. Welles, by the age of 23, had already shaken up Broadway with among other things his adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. At 24 he upset the entire nation with his War of the Worlds radio broadcast, which 1938 listeners took to be actual live reporting of an alien invasion. And just three years later, at 27, he directed what many cinema critics and scholars still consider to be the greatest film ever made, Citizen Kane. But as with so many iconoclasts, his work made him a number of enemies, both among Hollywood studios, who saw him as difficult if not impossible to work with, and in the political world, where William Randolph Hearst, the powerful newspaper magnate and the unnamed subject of Citizen Kane, did everything in his power to destroy Welles both personally and professionally.

The story – the “real” story – isn’t easy to follow. Welles shot the film off and on for over six years, recasting and re-shooting the much of it when actor Rich Little dropped out midway through production and going so far as to edit porn films when he needed his cinematographer Gary Graver back on Wind’s set and Graver was behind on his “day job”. The central figure in the film, the director Brooks Otterlake, is an acolyte of the even greater director Jake Hannaford (played by Welle’s close friend and celebrated director, John Huston). Part of Otterlake’s backstory is that he began his career as a film critic but became a great director in his own right and now struggles to move out of the shadow cast by his mentor. Otterlake is played by Peter Bogdanovich, who, when filming began on Wind was a well-known film critic. In fact, early on, Welles shot footage of Bogdanovich the film critic playing a film critic. But over the course of filming, Bogdanovich – like Otterlake — became an important filmmaker too, directing The Last Picture Show (1971) and began struggling to move out of the shadow cast by his own mentor, Welles himself. In the film Otterlake and Hannaford spar with one another in a relationship that is one part father and son and one part bitter rivalries. In real life, Welles and Bogdanovich would similarly fall out with one another, with Welles at one point publicly dismissing the younger man’s accomplishments and calling him “a pain in the neck.”

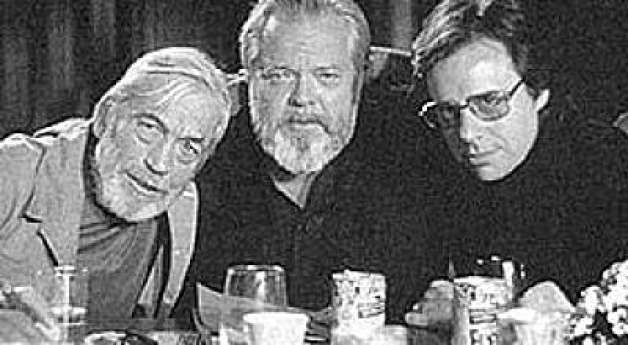

Three Directors: Welles, Huston, and Bogdanovich [Credit: SFGate]

Ultimately, the only fully edited copy of The Other Side of the Wind wound up in the hands of an Iranian businessman Medhi Boushehri, another in a long list of those who had agreed to fund Welles’s work only to watch helplessly as the director ran far over budget. When the Islamic Revolution happened in 1979, sweeping the Shah and the ruling oligarchy out of Iran, the film was tucked away in a vault with Bousherhri, demanding to recoup his money before he would release it. Welles sued for five years, until his death in 1985, to recover the copy, but to no avail. And that was that: the last statement of a man who had never truly been given his due as an artist, lost forever to history. Until in an unexpected turn of events in 1998, when Boushehri was, at last, prevailed upon to change his mind and release the film. Even so, it would be another 20 years, with Bogdanovich and others working painstakingly to restore the picture to what Welles had envisioned, before The Other Side of the Wind was finally released. That release came this past August at the Venice International Film Festival before the film was subsequently on Netflix, accompanied by a smart documentary on the whole affair, They’ll Know Me When I’m Dead, directed by Morgan Neville and narrated by Alan Cumming.

All of that is enough to make the film worth watching. Beyond the fascination of the mystery itself, all this background makes of the film a turning point in the history of filmmaking, both in a purely historical sense and in an artistic sense. Wind captures a singular moment in film history, a response to postmodernism, a response to new wave European cinema, a statement of its time; and yet that statement was put away, like a time capsule, to be examined only now, more than forty years later. What it means in those terms warrants an entirely different essay, or perhaps an entire book exploring Welles’s many complex and intersecting themes and thinking about this film as the final moment in a spectacular, if often difficult and certainly peculiar, career.

But never mind all that. Forget The Other Side of the Wind’s fascinating history; the way it mixed with life so that it becomes impossible to tell where film ends and life begins; its homage to European cinema; its deep roots in postmodernism; its relationship to Welles himself. Watch it because, as a film, it is brilliant.

I hope you liked this article and be sure to check out more of our content at ScreenHub Entertainment such as our spoiler-free reviews of Spider-Man: Into The Spiderverse or Aquaman.

2 thoughts on “The Other Side of the Wind Isn’t a Film You Watch; It’s a Film You Study – Screenhub Entertainment”